The evidence for weaning

Trying to understand the studies behind weaning guidance

Table of Contents

Two questions perplexed Tina and I:

- When to first introduce complementary foods for a breastfed baby?

- How should we handle the introduction of potentially allergenic foods to minimise risk of an allergy?

Lots of non-technical answers exist, like the ones on the NHS Start4Life website. And they often contain content that suggests interesting research lies behind the guidelines. For instance the following is on Start4Life:

You should wait until your baby is around 6 months old. [..] Evidence has shown that delaying introducing peanuts and hens' eggs after 6-12 months may increase the risk of developing an allergy to these foods.

Which leads to the question whether expsoure to an allergen at an early is protective against getting an allergy.

While my local state in Germany, true to Germanic form, gives the more precise suggestion to introduce different types of porridges between 17 and 26 weeks (5-7 months), but has a slight variation on the introduction of allergenic foods:

Neue Lebensmittel und Monat für Monat ein neuer Brei kommen hinzu. Zwischen dem Beginn des 5. Lebensmonats (17. Woche) und spätestens ab dem 7. Lebensmonat (26. Woche) ist der empfohlene Zeitraum für den Start. […] Ihr Immunsystem darf und soll gefordert, aber nicht überfordert werden. Die Beikost mit seiner schrittweisen Einführung verschiedener Lebensmittel ist ideal dafür. Beginnen Sie zwischen dem 5. und 7. Lebensmonat. Bis dahin wird das Baby ausschließlich gestillt oder bekommt eine hypoallergene Säuglingsnahrung (HA). Vorbeugend noch länger auf Beikost zu verzichten, schützt nicht vor Allergien und ist nicht sinnvoll.

With my favourite part of the Baden-Wurttemberg guidelines being the statement that you shouldn’t wait longer ‘as it doesn’t make sense’. The fact we have Baden- Wurttemberg guidelines also highlights the duplicity Germany federal bureaucracy - do parents in Bavaria really need a completely different set of guidlines to Baden-Wurtemburg.. 😭?

My favourite wording comes from Plunket, in New Zealand:

Delaying the introduction of the common allergy causing foods doesn’t prevent food allergy. Research shows that if you give your baby these foods before they turn one, it can greatly reduce the risk of them developing a food allergy. Even if you have a family history of food allergy or not, include common allergy-causing foods when you introduce other first solid foods, at around six months old. Add a new food every two to four days to give you time to notice any reaction.

All three talk about the introduction of allergenic foods as a way to prevent the onset of allergies for specific foods. Understanding where this comes from is something I wanted to dig into.

My aim

Summarise the guidelines I’d consider potentially relevant to me on when to start ‘complementary’ food (e.g. in addition to breast milk) and when and how to introduce allergenic foods. Then try to figure out if they are referencing the same literature.

Weaning

Guideline cheatsheet

| Organisation | Title | How long to stay with exclusive breast feeding | Earliest to start complementary feeding |

|---|---|---|---|

| WHO [Global] | Guiding principles for complementary feeding of the breastfed child | 6 months | 6 months |

| NHS Start4Life [UK] | Ready or not? [For weaning] | 6 months | 6 months |

| Plunket [NZ] | Introducing solids | 6 months | 6 months |

| AAP [US] | What is weaning and how do I do it? | 4 months | 4 months |

| My German State | Von Anfang an mit Spaß dabei – Essen und Trinken im ersten Lebensjahr | 6 months | 6 months |

Baby led weaning

There are a lot opinionated parents that blog (myself included…). With one genre that often irks me being the ‘mummy blogs’ that push fads in how to raise your children. These blogs tend to have an affinity to a form of weaning called ‘Baby Led Weaning’. The general idea is you skip feeding pureed foods, and instead jump straight to finger foods. Pros: build coordination skills and skip having to puree foods, Cons: your baby chokes or misses out on nutrients (as the food doesn’t make it into their mouths).

New Zealand doesn’t recomend Baby Led Weaning.

Currently, very little research has been done on baby-led weaning. Before the Ministry of Health could recommend baby-led weaning to the public as a safe alternative to current advice, it would need evidence that baby-led weaning doesn’t lead to babies being iron-deficient, not growing well, or having an increased chance of choking

While the NHS is a bit more lenient with the following under the title of baby led weaning about Baby Led Weaning:

There’s no right or wrong way. The most important thing is that your baby eats a wide variety of food and gets all the nutrients they need.

Looking at the guidelines it seems that - there is no evidence of a benefit, but the potential harm (from choking) is also unproven. So you can either trust anecdotes from other parents and mummy blogs, or stick to pureed foods.

Decreasing the risk of allergies

Allergenic foods

According to NHS Start4Life these are the foods we are talking about:

- cows’ milk (in cooking or mixed with food)

- eggs (eggs without a red lion stamp should not be eaten raw or lightly cooked)

- foods that contain gluten, including wheat, barley and rye

- nuts and peanuts (serve them crushed or ground)

- seeds (serve them crushed or ground)

- soya

- shellfish (don’t serve raw or lightly cooked)

- fish

Should the mum avoid foods when breast feeding?

Both the AAP1 and European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology’s (EAACI) guidelines2 suggest that there is no evidence that a mother should worry about what she is eating, in terms of impacting the chance of her child gaining an allergy.

Digging into the EAACI reference, they cite a 2013 review3 that states there were two non-randomised studies that showed no effect. So it’s a case of ‘no evidence after limited research’ rather than a case where we can confidently reject the null and say mothers diet while breastfeeding has no impact.

When to introduce allergenic food?

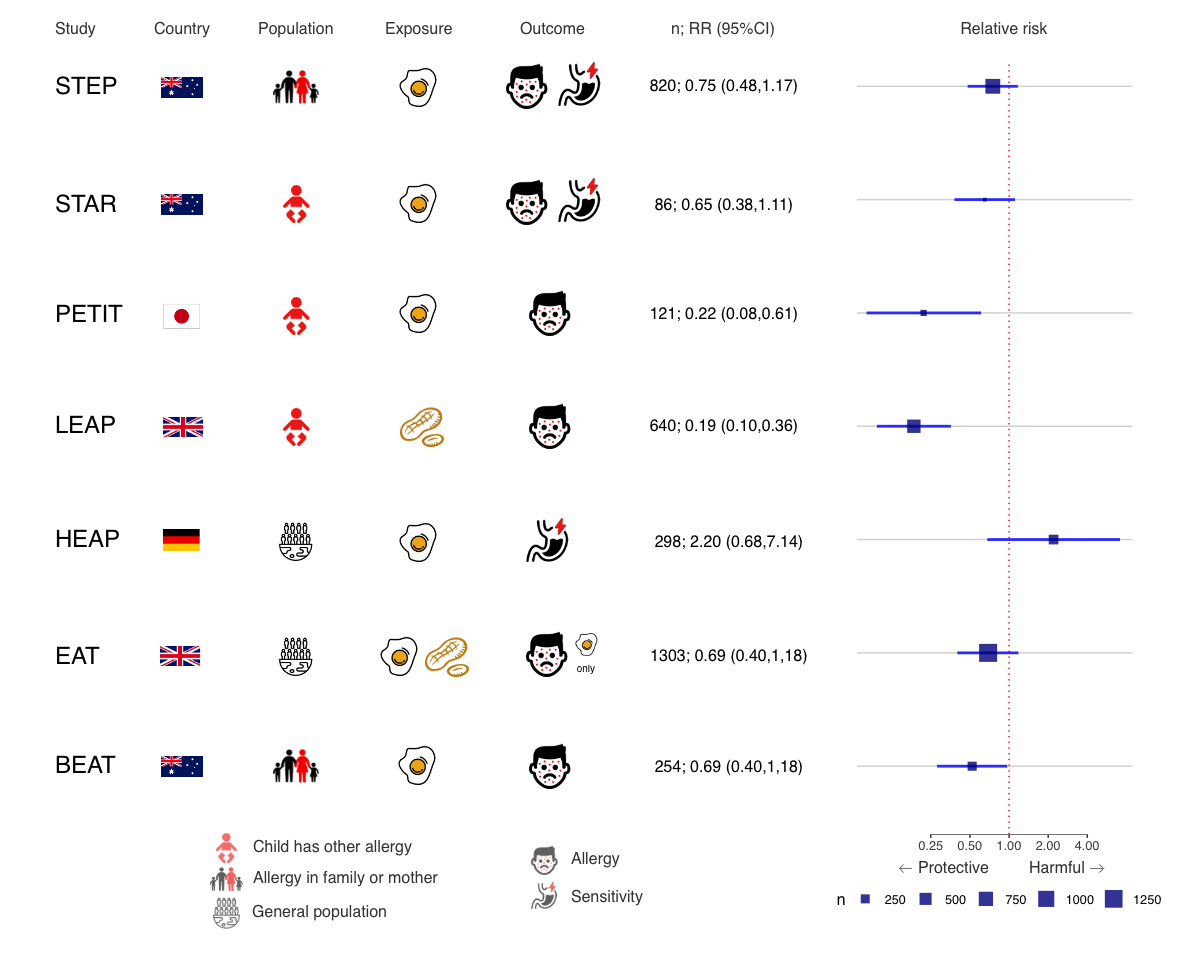

In the following figure I’ve tried to summarise the 7 most relevant studies looking at whether introducing allergens in the first year of life decreases the risk of having an allergy in early life.

In summary, PETIT, LEAP and BEAT were the only statistically significant studies to suggest earlier exposure (starting around 4-6 months) was protective from egg allergy (or peanut for LEAP), but there was general trend towards a protective effect across all but one study.

The complicating factor was that the populations were different. PETIT and LEAP were babies at risk of an allergy and BEAT were babies with a familial risk. EAT was a general population study - and while the central estimate was protective, it was not statistically significant. Taking this into account, it becomes a bit clearer where the 2019 AAP guidelines1 are coming from when they include the statement below (itself a summary of a more specific guideline they endorsed):

Infants with severe eczema, egg allergy, or both (highest risk) should have peanuts introduced as early as between 4 and 6 months of age (peanut allergy testing before introduction is recommended). This highest-risk group is the only one for which testing for peanut allergy is recommended. For infants with mild to moderate eczema (less risk), peanuts should be introduced as early as 6 months of age. For infants with no history of eczema or food allergy (lowest risk), peanuts should be introduced when age appropriate and in accordance with family preferences and cultural practices.

For a deeper dive, below is some of the underlying data I used to make the figure above. The Population and Intervention columns highlight the heterogeneity between studies.

| Study (YEAR) | Trial type | Population | Intervention group | Control group | Outcome | Assessment age (m) | Relative Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAR (2013)4 | Blinded | Moderate-severe eczema | 6.3g egg powder | Rice powder | Egg allergy or sensitization | 12 | 0.65 (0.38,1.11) |

| LEAP (2015)5 | Open label | Moderate-severe eczema and/or egg allergy | 6g peanut | No peanuts till 60m | Peanut allergy | 60 | 0.19 (0.10,0.36) |

| EAT (2016)6 | Open label | General | 4g various | Breast feeding only till 6 months | Egg allergy | 12 to 36 | 0.69 (0.40,1.18) |

| HEAP (2017)7 | Blinded | General | 7.5g egg white powder | No egg with rice powder | Egg sensitization | 12 | 2.20 (0.68,7.14) |

| STEP (2017)8 | Blinded | Mother has allergy | 2.8g egg powder | Rice powder | Egg allergy or sensitization | 12 | 0.75 (0.48,1.17) |

| BEAT (2017)9 | Blinded | Allergy in family | 2.45g egg powder | Rice powder | Egg sensitization | 12 | 0.52 (0.28,0.97) |

| PETIT (2017)10 | Blinded | Atopic dermatitis | 0.175g for 3 months, then 0.875g for 3 months | Squash powder | Egg allergy | 12 | 0.22 (0.08,0.61) |

LEAP’s impact

One interesting thing to note was the impact of randomised trials and particularly the LEAP study5 on disproving earlier assumptions. Back in 2000 the guidelines from AAP where to delay peanuts, which then switched to ‘do not delay’ in 200811, before coming the current ‘should be introduced’ in 2019. The following video is a summary of LEAP by the New England Medical Journal.

JAMA meta-analysis

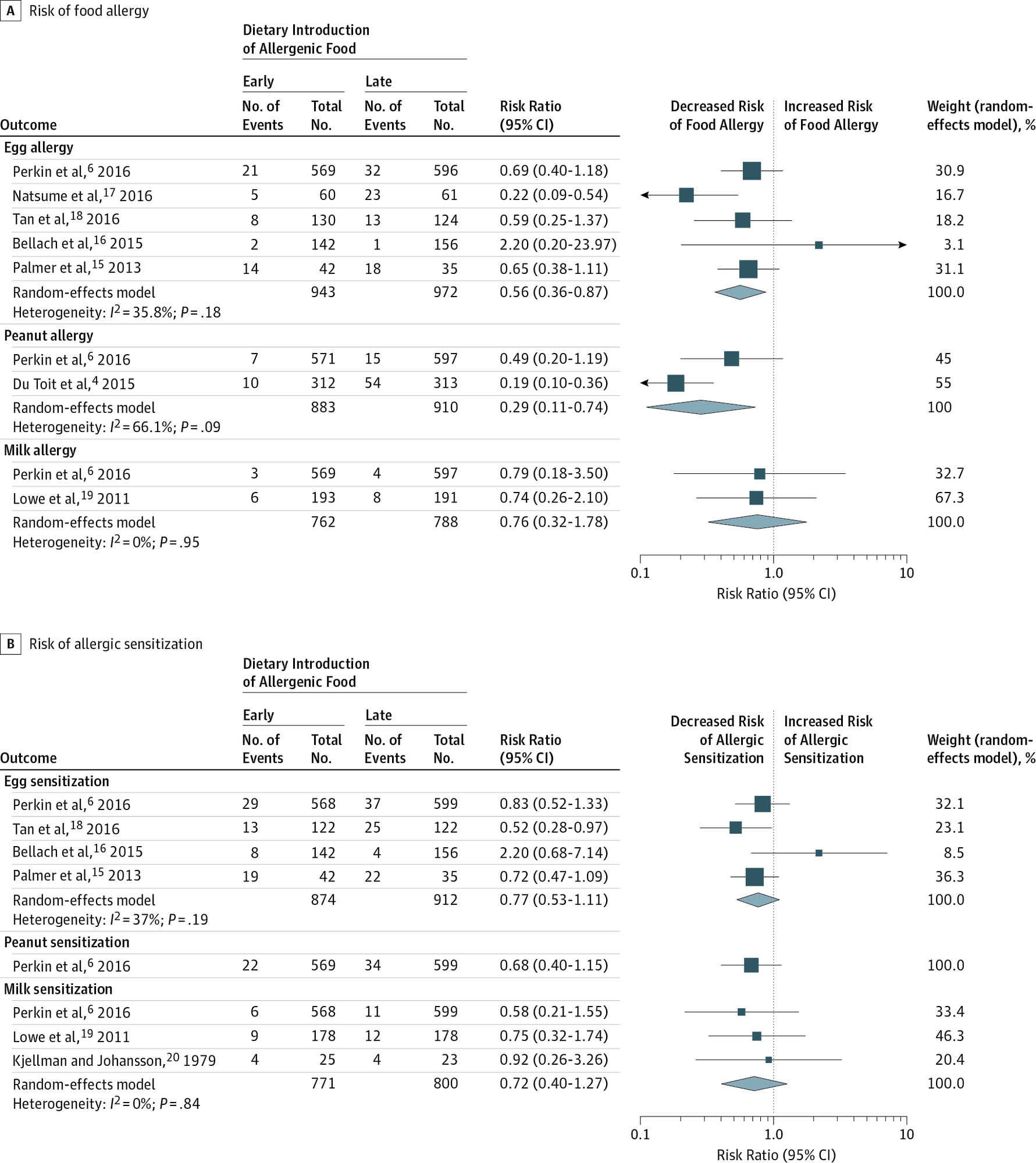

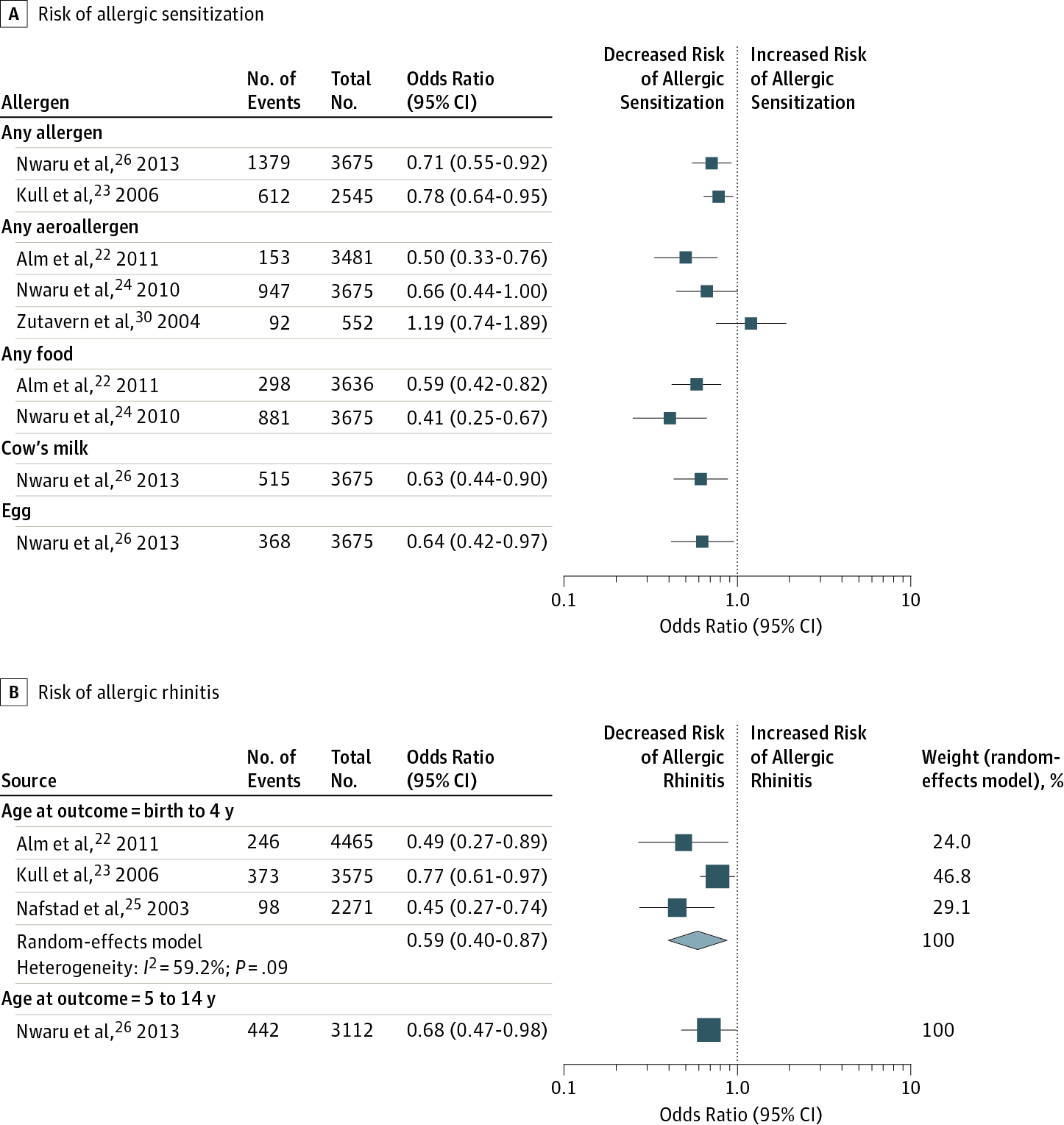

A 2016 meta-analysis published in JAMA12, aimed to ‘To systematically review and meta-analyze evidence that timing of allergenic food introduction during infancy influences risk of allergic or autoimmune disease’.

While this is an older meta-analysis, we still see that general trend where the central estimate suggests that earlier exposure to an allergenic food is protective against having an allergy.

This second figure from the JAMA paper looks at the introduction of fish, and it’s effect on allergenic responses.

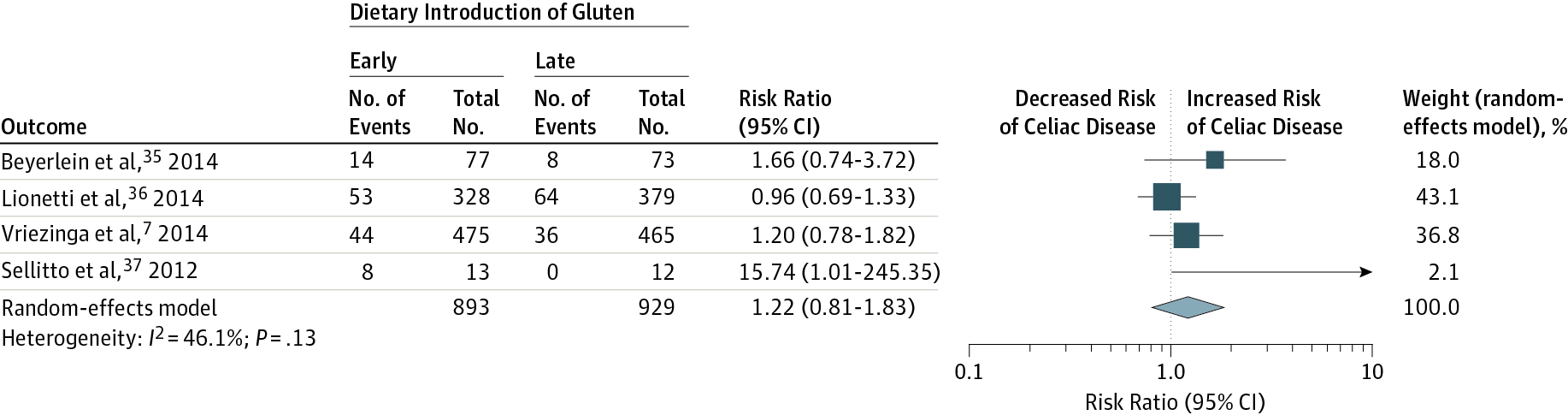

Things become less clear with gluten - where early introduction doesn’t seem to consistently suggest a decreased risk of celiac disease. Suggesting that earlier exposure to fish, egg and milk is most likely beneficial - but it’s apperant gluten exposure doesn’t have any suggestion of a benefit in the literature.

My conclusions

Summarising guidelines

- It’s great to keep exclusively breastfeeding to 4 months (or later) if possible.

- After 4 months at the earliest but 6 months at the latest, time to start introducing complementary foods.

- Try to introduce a new ‘allergen’ once every 3-4 days and look out for reactions. In the studies, they are often talking about small amounts (e.g. 4g peanut butter mixed into carrot puree or porridge). Celiac disease though doesn’t currently have evidence of being connected to the timing of when it’s introduced (to date).

The evidence

The evidence to date behind these guidelines is something that needs further replication. Comparing the best evidence in 2000, vs 2019 we have seen a total reversal from a recomendation to delay introducing allergenic foods, to now introducing them when the baby first moves off milk.

The shift seems to be tied to a move from relying on expert opinion, to relying on randomised controlled trials - which I guess suggests that the current recomendations are fairly stable, and unlikely to swing back to a recomendation to avoid foods like peanuts again.

For a more detailed break down of how to apply these principles, the blog scienceofmom.com has a nice summary of the EAT intervention (and her post was one of the inspirations for me writing this post). You can get to it via this link.

Appendix

References

European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology’s (EAACI) 2014 Guidelines for Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Prevention ↩︎

de Silva et al, Primary prevention of food allergy in children and adults: systematic review. Allergy 2014; 69: 581–589. ↩︎

Palmer et al. Early regular egg exposure in infants with eczema: A randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013 Aug;132(2):387-92.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.05.002. Epub 2013 Jun 26. PMID: 23810152. ↩︎

Du Toit G et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2015 Feb 26;372(9):803-13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414850. Epub 2015 Feb 23. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2016 Jul 28;375(4):398. PMID: 25705822; PMCID: PMC4416404. ↩︎

Perkin et al. Randomized Trial of Introduction of Allergenic Foods in Breast-Fed Infants. N Engl J Med. 2016 May 5;374(18):1733-43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1514210. Epub 2016 Mar 4. PMID: 26943128. ↩︎

Bellach et al. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of hen’s egg consumption for primary prevention in infants. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017 May;139(5):1591-1599.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.045. Epub 2016 Aug 12. PMID: 27523961. ↩︎

Palmer et al. Randomized controlled trial of early regular egg intake to prevent egg allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017 May;139(5):1600-1607.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.052. Epub 2016 Aug 20. PMID: 27554812. ↩︎

Wei-Liang Tan et al. A randomized trial of egg introduction from 4 months of age in infants at risk for egg allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017 May;139(5):1621-1628.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.08.035. Epub 2016 Oct 11. PMID: 27742394. ↩︎

Natsume et al. Two-step egg introduction for prevention of egg allergy in high-risk infants with eczema (PETIT): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017 Jan 21;389(10066):276-286. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31418-0. Epub 2016 Dec 9. PMID: 27939035. ↩︎

Greer et al. Effects of early nutritional interventions on the development of atopic disease in infants and children: the role of maternal dietary restriction, breastfeeding, timing of introduction of complementary foods and hydrolyzed formulas. Pediatrics. 2008;121(1):183–91. ↩︎

Ierodiakonou D et al. Timing of Allergenic Food Introduction to the Infant Diet and Risk of Allergic or Autoimmune Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(11):1181–1192. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.12623 ↩︎